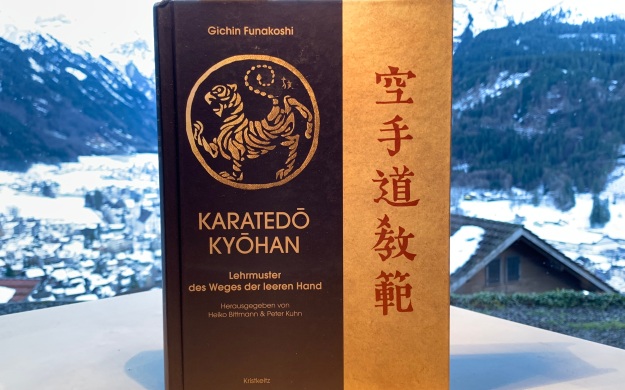

The first German translation of Funakoshi Gichin’s third book, Karatedō Kyōhan 空手道教範 (1935), has just been published. Lehrmuster des Wegs der leeren Hand was published by Werner Kristkeitz in Heidelberg, a publisher that has made a name for itself in Germany by publishing literature on Zen, Buddhism and Asian martial arts.

For almost two years, a project team under the scientific lead of university professors Heiko Bittmann and Peter Kuhn, sports scientists and proven experts in the field, was busy translating the book and placing it in the appropriate historical and sports science context in countless commentaries and footnotes on over 30 pages.

Funakoshi Gichin 船越義珍 (1868–1957) is considered by many to be the “father of modern karate”, although the origin of this term cannot yet be clearly traced. His literary work (in addition to a total of five books, he also published a large number of other publications) and his tireless work were decisive in enormously increasing the popularity of karate in Japan and ensuring its spread.

Karatedō Kyōhan is considered to be Funakoshi’s representative work from this period and is also “one of the most important early publications on karatedō” ever, as the two editors state in their introduction. The book was first translated into English in 1973 by Ōshima Tsutomu 大島劼 (born 1930) based on the Japanese new edition of 1958. The English translation of the first edition from 1935 was created by Harumi Suzuki-Johnston in 2005.

But why now a German translation directly from the Japanese original? Bittmann and Kuhn answer this by saying, among other things, that Funakoshi’s important book has not yet been available in German. Other arguments they put forward for their current work are also valid. In fact, there are far too few good, scientifically based works in German. Although there have been a large number of progressive works in the Anglo-American language area for many years that clear up myths and incorrect interpretations, only a few pioneers can be identified in the German-speaking world (for example, the works of Heiko Bittmann and Henning Wittwer are worth highlighting).

Unfortunately, when dealing with karate, too often reference is made to works from the 1990s. However, these mostly contain historical inaccuracies and a lack of knowledge of the Japanese language, and are therefore incorrect and misleading on a variety of levels.

German japanologist Andreas Niehaus had already pointed out this fact in his review of Bittmann’s dissertation in 2000. At the time, he stated that well-founded Japanese studies are required in the field.

This work is undoubtedly one of these. It sets standards in the translation of contemporary martial arts literature and is crucial in giving karate practitioners and interested parties a better understanding of the historical background and development of Japanese karate. The editors of this book are to be thanked for this. The book is a very solid work. Reading it is highly recommended.

Leave a Reply