For the academic study of karate, it is always important to think outside the box. I regularly look to see what’s new on the publication market and what scholarly approach the authors have chosen for their research of other martial arts disciplines.

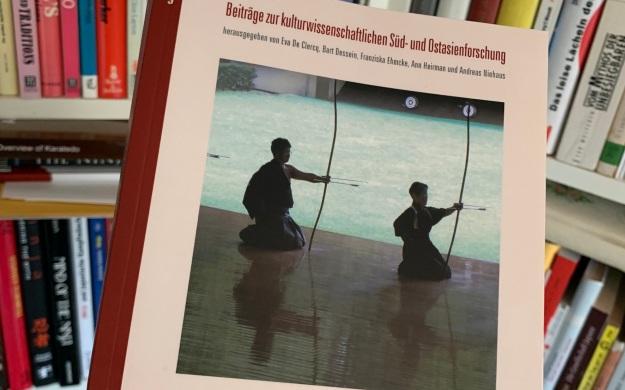

Kyūdō 弓道 or the “way of the bow” is the art of Japanese archery. Like other systems with the suffix “dō”, such as iaidō 居合道, jūdō 柔道 and kendō 剣道, kyūdō also developed from the Japanese martial arts. Compared to Olympic archery, the Japanese system is characterized by slow, ceremonial movements, traditional clothing, handmade bamboo bows and bamboo arrows.

But is kyūdō a (popular) sporting discipline or an art form? What role do mysticism and religiosity play in this? And how has the understanding of it changed over the decades? Rita Németh, a Japanese studies graduate, explored these questions in her inaugural dissertation “Wertewandel und Wandel der Selbstdarstellung im japanischen Kyūdō von der Taishō-Zeit bis zur Gegenwart“ (Changing values and the transformation of self-expression in Japanese Kyūdō from the Taishō period to the present) at the Faculty of Philosophy of the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn (2018). The book discussed here is based on this.

However, anyone hoping for an insight into a spiritual kyūdō theme will be disappointed. Drawing on the analysis of the cultural scientist Yamada Shōji, first published in Japanese in 1999, Németh rightly refers right at the beginning to the mythical connection between kyūdō and zen buddhism constructed by Eugen Herrigel (1884–1955) in his book “Zen in der Kunst der Bogenschießen“ (Zen in the Art of Archery), published in 1948. In this context, Németh aptly emphasizes that the view of a spirituality of kyūdō falls far too short and ignores many other facets (pp. 24–).

The fact that kyūdō should not be viewed one-dimensionally is then impressively demonstrated in the further course. Németh analyzes the various cultural, philosophical and sporting aspects of kyūdō in their historical transformation using scientific methodology and drawing on a comprehensive source base of Japanese, English and German literature.

Anyone who studies East Asian fighting methods and systems cannot avoid dealing with the concept of sport. However, caution is required because, as Martin Filla stated in his dissertation on the fundamentals and essence of ancient Japanese sports arts” (1939, p. 5), it should not be forgotten that the old systems “were not understood and practiced as sports in the Western sense”. Even if his further description is strongly ideologically tinged and presumably based on Herrigel, Otto Kollreutter (1943, p. 7) also points this out aptly when he writes „one cannot describe the old Japanese sports of judo (jiu-jitsu), fencing (kendo), wrestling (sumo) and above all archery (kyudo) as pure sport in our sense”. For this reason, Németh defines the theoretical basis of her study using the key concepts of “sport”, “movement culture”, “values”, “norms”, “goals”, “changing values” and “cultural transfer”. To this end, she draws on publications that “focus on research into values and their change in a society’s sport and exercise culture” (p. 53).

As announced in the title, the author then looks at the subject of her research from the beginning of the 20th century to the present day, but not without giving the reader an insight into the pre-modern development of kyūdō and the various forms of Japanese archery (pp. 91–). Her analysis begins in 1900, a time in which the Japanese empire, after its victory in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), was proudly pushing ahead with its militarization. Németh then looks at the Taishō period (1912–1926) up to the Second World War (pp. 103–) and the development of kyūdō since the end of the Second World War (pp. 133–).

An essential part of her work is the content analysis of hundreds of kyūdō magazines of the Greater Japan Kyūdō Association Dai Nippon Kyūdōkai 大日本弓道会 and the Zen Nihon Kyūdō Renmei 全日本弓道連盟. On this basis, she can categorize the kyūdō for the 1920s as an “elegant means of cultivating life”. In the 1920s and 1930s, according to her research, kyūdō was then seen as a “domestic sport and moral education”. In the 1930s, Németh notes a transition to the perception of kyūdō as a “means of physical and mental training”. After the Second World War and a ban on kyūdō as part of the ban on all martial arts in Japan by the occupying powers, kyūdō was mainly practiced in the 1950s under the label “Budō of Peace”. In the following decades, it is then seen as an “elegant art of Eastern philosophy” (1950–1960s) and a “national sport to promote health” (1960–1970s). In the 1980s, kyūdō was seen as a “critique of outdated ideals”, in the 1990s it was seen as a “path to personality development and self-realization” and finally in the 2000s as a “sport for a happy lifestyle”.

With this categorization, Németh demonstrates for the first time empirically the change in values in Japanese kyūdō in the period she has defined.

Conclusion:

In 2000, German Japanologist Andreas Niehaus had already aptly written in his review of Heiko Bittmann’s publication “Karatedō. Der Weg der leeren Hand. Meister der vier großen Schulrichtungen und ihre Lehre“ (Karatedō. The way of the empty hand. Masters of the four major schools and their teachings) (1999), that well-founded Japanese studies are required in the field of East Asian martial arts.

With her book, Németh presents just such a work. In her unique study of Japanese archery, she comprehensively documents how kyūdō and its values were perceived in Japan during the 20th century. In doing so, she illustrates how this understanding was subject to constant change over a period of more than 100 years. The result is an outstanding academic work that offers high-quality reading for kyūdō adepts, sports and body culture researchers and martial arts enthusiasts.

In addition, Németh’s work provides an important impulse: the question of how the perception of a martial art changes over time should definitely also be discussed to an appropriate extent for other Japanese budō disciplines. For example, a corresponding examination of karate(-dō), which originally came from the Ryūkyū Islands, would be an important addition. It was introduced from a privately practiced method in pre-modern times into the Okinawan school curriculum in 1905 and taught at Japanese universities from 1924 onwards. Its further path via its connections to a growing militarism in Japan led to its national and international sportification and finally to an Olympic discipline. Németh undoubtedly provided an important blueprint for this.

Sources:

Filla, Martin (1939): Grundlagen und Wesen der altjapanischen Sportkünste (Fundamentals and essence of the ancient Japanese sports arts). Würzburg-Aumühle: Konrad Triltsch Verlag (in German)

Kollreutter, Otto (1943): Japaner (The Japanese). Berlin: Luken & Luken (in German)

Yamada, Shōji (2001): The Myth of Zen in the Art of Archery, in: Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 28/1-2

Leave a Reply