There have been repeated attempts to compare karate, especially kata from different styles, in order to draw conclusions about their origin or lineage. However, the methodical approach of analysing the movements and execution of kata has its weaknesses, because kata was and is not a fixed construct over time. Karate (and therefore kata) is constantly changing. Everything changes. Karate is also changing – in some places more slowly, in others more rapidly. This change can be observed particularly well in international competitive karate.

An impressive example is the karate of Funakoshi Gichin (1868–1957), for which there is photographic material for example from 1925 and 1936, that allows a comparison of the practice of a senior karate personality. Here you can see very clearly that the movements alone have changed within a very short time, even if only slightly at first.

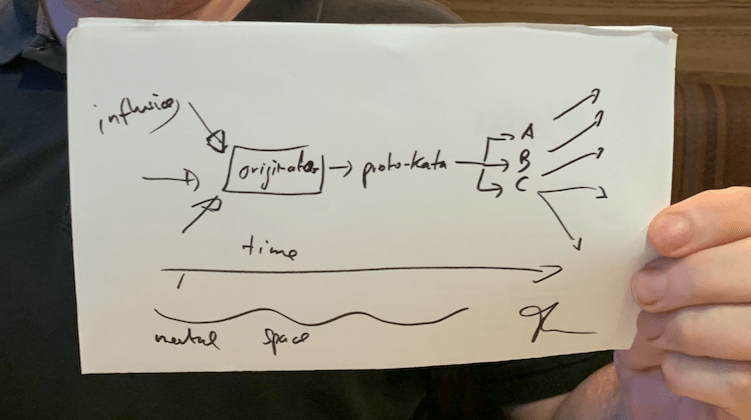

But why and how does karate change, which is especially reflected in the kata?

I have already touched on this subject briefly in my Itosu book (2021). Building on this, I am convinced that all approaches to compare kata in their historical evolution – without a solid foundation such as historical records and images – are, from a scientific point of view, only extremely hypothetical and thus susceptible to conclusions in the wider historical discourse.

The most important reason for this is that techniques and sequences in kata have been and are being changed either (1) intentionally or (2) unintentionally. This makes any analysis very difficult.

1.1 Deliberate changes to mitigate dangerous techniques

There are many reasons for making deliberate changes. Movements and techniques have been altered, shortened and simplified – for example, to make them easier to integrate into school lessons. At the beginning of the 20th century, school authorities seemed to be concerned with mitigating for young students a variety of fighting techniques that had once been developed for defence and fighting to the death. As suggested by Hanashiro Chōmo (1869–1945) in his remarks on the knife hand (Kinjō 1956), his student Kinjō Hiroshi (1919–2013) explains in this context that the ‘anti-social’ or dangerous techniques of karate had been changed to a more modest character and modified towards safety and conformity for educational purposes. In line with the ideals of modern physical education, life-threatening techniques seemed to have been replaced: Finger punches to the eyes became regular punches, and kicks to the testicles were performed higher to provide more exercise. Even kata were not spared from this process. Kinjō pointed out: “We practised these kata like gymnastics. All the dangerous techniques like groin kicks were taken out” (Curtis 2001).

1.2 Deliberate changes to differentiate from others

Techniques and procedures are also said to have been taught one way to some students and another way to others. Only one way was said to have been the true line of transmission, with which future generations could distinguish themselves and prove their “true“ lineage.

1.3 Deliberate changes to improve movements

It is also important to consider when – i.e. at what age and point of time – a teacher taught his students. Over the years, they themselves may have made adjustments (even if only nuances) to their kata because they thought the procedures were better suited to them and their students.

1.4 Deliberate changes for better public presentation

In the context of modern competition, it should not be forgotten that some kata sequences are adapted to make them more attractive to spectators and judges.

2. Unintentional changes

It should also be noted that many masters were no longer able to perform kata in the way they might have in their youth. Not least for orthopaedic reasons, they practised techniques differently. Students who were taught by them in their youth will have adopted this style of execution. Students at a later age may have learnt different movements to a certain extent.

Last but not least, small ‘mistakes’ may have crept in during the study of techniques, which were overlooked by their masters during instruction, and which they in turn passed on to their own students. This is more likely to happen if a teacher is teaching more than a handful of students, who for various reasons may not have been able to attend regular training.

3. Conclusion

Based on the above, it is always difficult to say: this is the kata of Master A, that is the kata of Master B. I am of the opinion that the form cannot only be attributed to a specific person, but also to a specific point in time. An example could be: This is the kata of Master A from 1905 – because in 1935, this kata of Master A may have turned out a little – even if only marginally – differently.

References:

Curtis, Robert (2001): An Interview with Sensei Hiroshi Kinjo, in: Traditional Karate, July, pp. 12–17

Feldmann, Thomas (2021): Ankō Itosu. The Man. The Master. The Myth. Biography of a Legend. Düsseldorf: Lulu Press

Kinjō, Hiroshi (1956): 平安の研究 Pin’an no kenkyū (Study of Pin’an), Part 1, in: Gekkan Karatedō, June, Karate Jiho-sha, pp. 49–52 (in Japanese)