Hanashiro Chōmo (1869–1945) played a significant role in the development of modern karate. Despite his importance, he remains underrepresented in historical discourse. Fortunately, several written sources preserve his legacy. I recently came across one such example in the 1997 publication 沖縄の昔面影 Okinawa no mukashi omokage (Remnants of Old Okinawa), in which the author, Kinjō Kazuhiko 金城和彦 (1923–?), evokes a nostalgic reflection on Okinawa’s past. In regard to Hanashiro, he writes:

[…] By the way, there is a term called “kakuribushi” (カクリブシ). It refers to someone who possesses strength or skill but does not boast or show it off, and whose name is not widely known in society. In other words, when an unexpected person demonstrates surprising ability, people would refer to them as a kakuribushi.

For example, in a shima (Okinawa’s traditional style of wrestling) tournament, if an unknown competitor defeats a well-known and widely respected wrestler (シマトゥヤーShimatuyaa) against all expectations, people would cheer them on as a “kakuribushi.”

The term kakuribushi is also used in other situations. For instance, at an entertainment gathering, if someone who usually keeps quiet unexpectedly shows a hidden talent and wins applause, they too are called a kakuribushi. In any case, kakuribushi refers to someone who has real ability but keeps it hidden and does not show it on the surface. The term itself conveys a sense of the person’s character and integrity. The great karate master Funakoshi Gichin (who was my uncle) once expressed the famous maxim, “There is no first attack in karate.” (空手に先手なし karate ni sente nashi). Karate is a martial art. It must not be used recklessly or in quarrels. “No first attack” means that even if provoked, you must not strike first—it is only in situations of real danger, as a means of self-defense, that one may use their skills.

In Asato, there once lived a great karate master from Shuri named Hanashiro no Tanmē (Old Man Hanashiro). When I was in middle school, I studied karate under this Tanmē. One day, when Tanmē was walking along Makan Road (the road that now runs from around the present-day Kōnan High School to Asato), some young men who didn’t know he was a karate master tried to pick a fight with him. Without showing any fear, Tanmē simply said, “Wait a moment,” and then casually picked up a large stone that was lying nearby and held it up. The young men realized there was no way they could do the same, and said, “This guy’s strong!“, before turning tail and fleeing. This was truly a case of “no first attack in karate”, and how the warriors of old were people of great character.

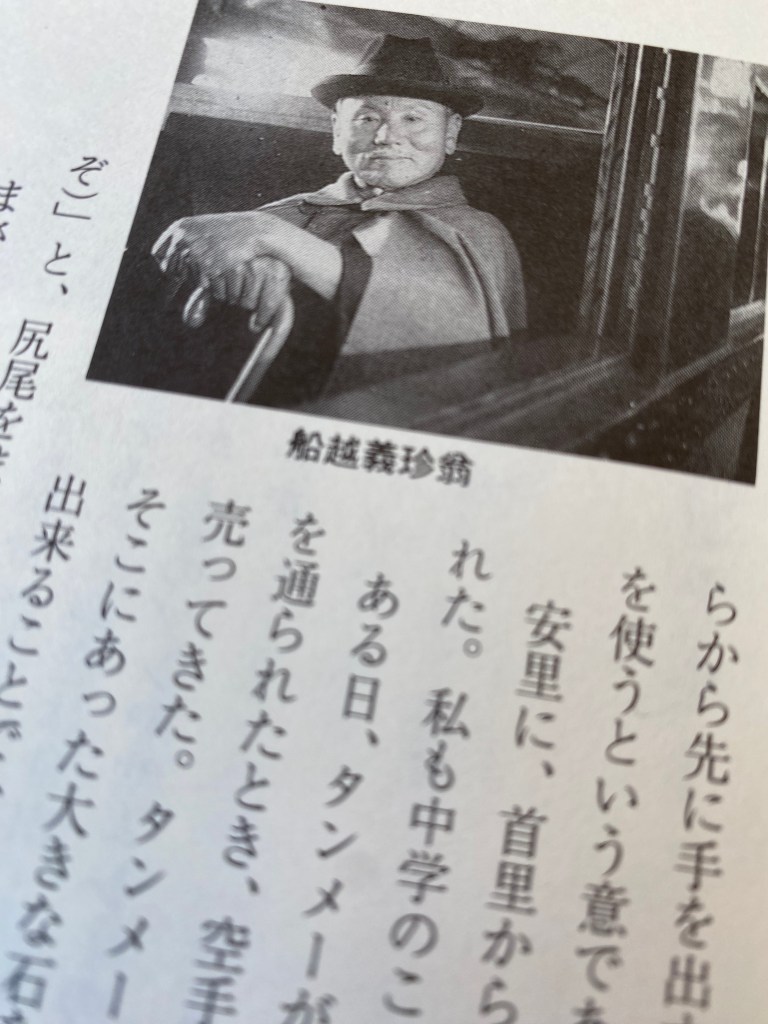

The book also includes a photograph of Funakoshi Gichin (1868–1957) that I had not encountered before.

Kinjō Kazuhiko graduated from Okinawa Prefectural First Junior High School in 1941. He later moved to Tōkyō, completing his studies at the Tōkyō University of Education (now the University of Tsukuba) in 1947. He pursued a career in education and taught at Kokushikan University in Setagaya, Tōkyō, retiring in 1994. According to his biography, he held a 6th dan in Kōdōkan jūdō and the title of Shihan in Shōtō-ryū karatedō. As an author, he published numerous works between 1959 and 1997, with a focus on Okinawa. Apparently, he was a nephew of Funakoshi Gichin.

Sources:

Kazuhiko, Kinjō (1997): 沖縄の昔面影 Okinawa no mukashi omokage (Remnants of Old Okinawa). Naha: Naha Shuppansha, pp. 20–21

Nakasone, Genwa (ed.): 空手道大観 Karatedō Taikan. Tōkyō: Tōkyō Tosho

Image AI-generated with chat.openai.com – Public Domain Mark