Kanō Jigorō (嘉納治五郎, 1860–1938) undertook a visit to Okinawa and Kyūshū in 1927. Although no photographs of the trip are known to exist today—indeed, the Kōdōkan Archives has no record of any—it was prominently documented in the Kōdōkan publication Sakkō, No. 3 (1927), which featured a detailed account of Kanō’s stay.

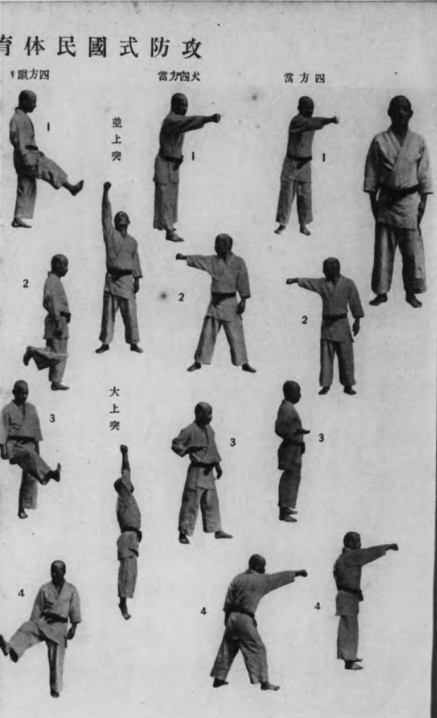

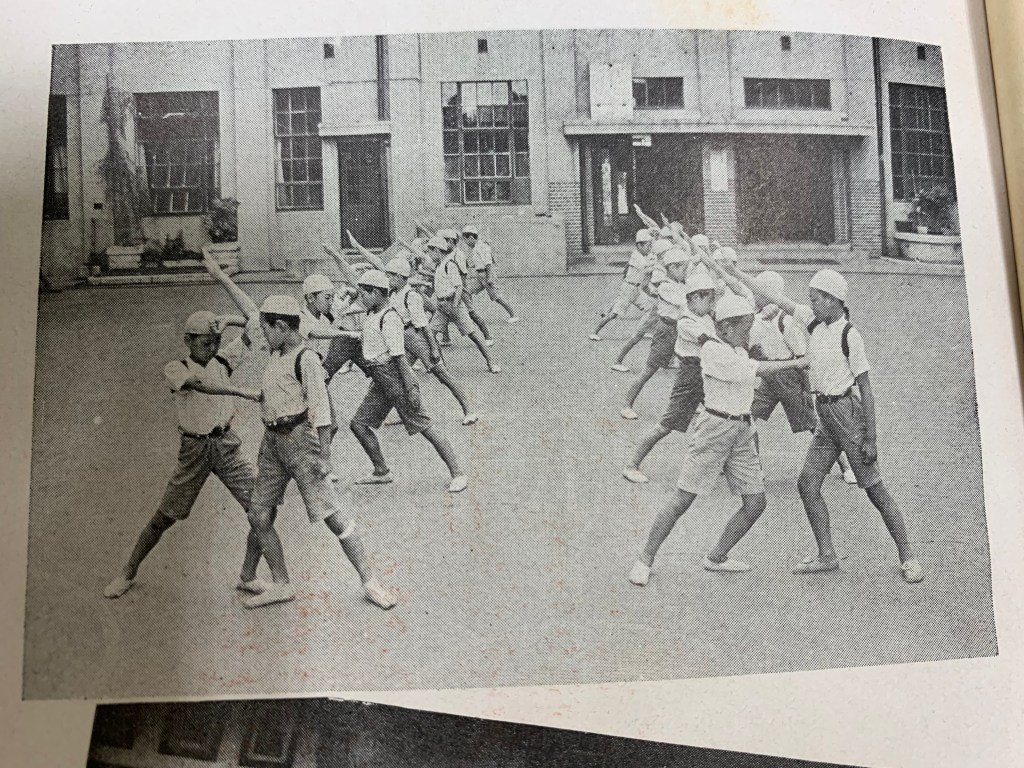

Interestingly, just two issues later, in Sakkō No. 5 (1927), a photograph appears of jūdōka practicing what appears to be stances and strikes similar to karate. Was this merely a coincidence, or might Kanō have brought back ideas from his visit to Okinawa to the Japanese mainland? By that time, he was already familiar with karate through various earlier encounters, most notably when he invited Funakoshi Gichin (船越義珍, 1868–1957) to demonstrate karate at the Kōdōkan in 1922.

Sakkō No. 5 (1927)

Jūdō historian Lance Gatling (www.kanochronicles.com) explained in a Facebook post last year that this type of practice is referred to as Kōbōshiki Kokumin Taiiku (攻防式国民体育)—an “attack and defense” form of national physical education. According to Gatling, these exercises were developed by Kanō and his associates as early as 1924, prior to his 1927 trip to Okinawa. However, one need not be an expert to notice that the techniques depicted in the 1927 issue of Sakkō resemble the forms of karate that Funakoshi Gichin had been teaching in mainland Japan since 1922.

According to the Kōdōkan website, this system is described as …

… an offensive and defensive form that integrates physical education and martial arts, consisting of both solo and paired movements. It was developed by Master Kanō based on the principle of the maximum efficient use of energy (seiryoku zen’yō 精力善用). Seiryoku Zen’yō National Physical Education was created in 1924 as a national physical education method rooted in the art of attack and defense. Its purpose is to teach the proper way to cultivate both body and mind through the practice of offensive and defensive techniques such as striking, hitting, and kicking…

A short film demonstrating several techniques from Kōbōshiki Kokumin Taiiku is available online.

Was Kanō and his team’s development of these practices a deliberate response to the fighting forms introduced from Japan’s southernmost prefecture, aimed at offering a comparable alternative? Or was it part of a broader effort to make Kōdōkan Jūdō more comprehensive?

Kanō’s primary intention appears to have been the creation of a systematic physical training method for the general public, integrating martial elements with educational goals. He sought an ideal synthesis of physical and moral cultivation, drawing on various forms of movement and discipline (Niehaus 2003: 255). In 1927, he eventually introduced his new system, which he subsequently revised in 1930, rebranding it as national physical exercise according to the principle of the most effective use of energy (ibid.).

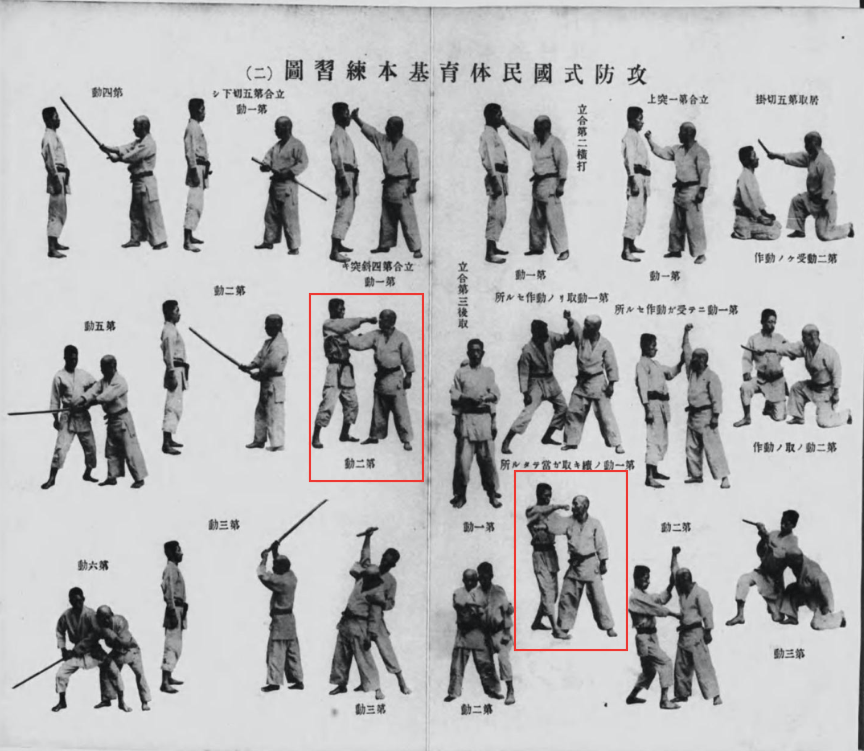

Following the 1927 publication of Sakkō, which showed a group practicing, a more comprehensive textbook was issued in 1928 by the Kōdōkan Bunkakai. This volume elaborated on the physical exercises developed by Kanō Jigorō, combining explanatory text with illustrations. Significantly, it was designed to allow practitioners to study and learn the system independently, without direct instruction (ibid., 256).

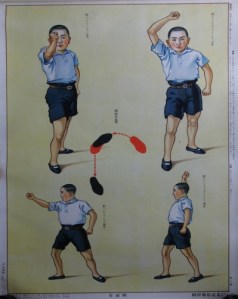

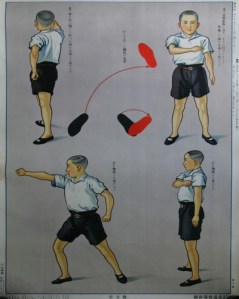

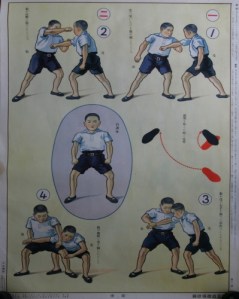

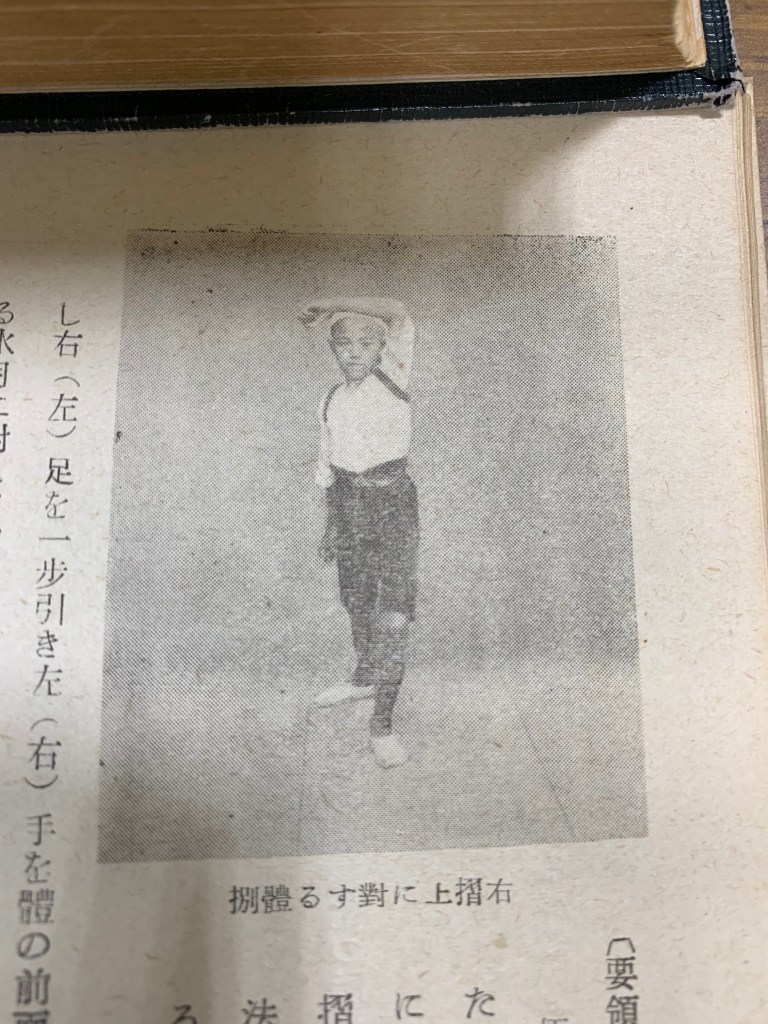

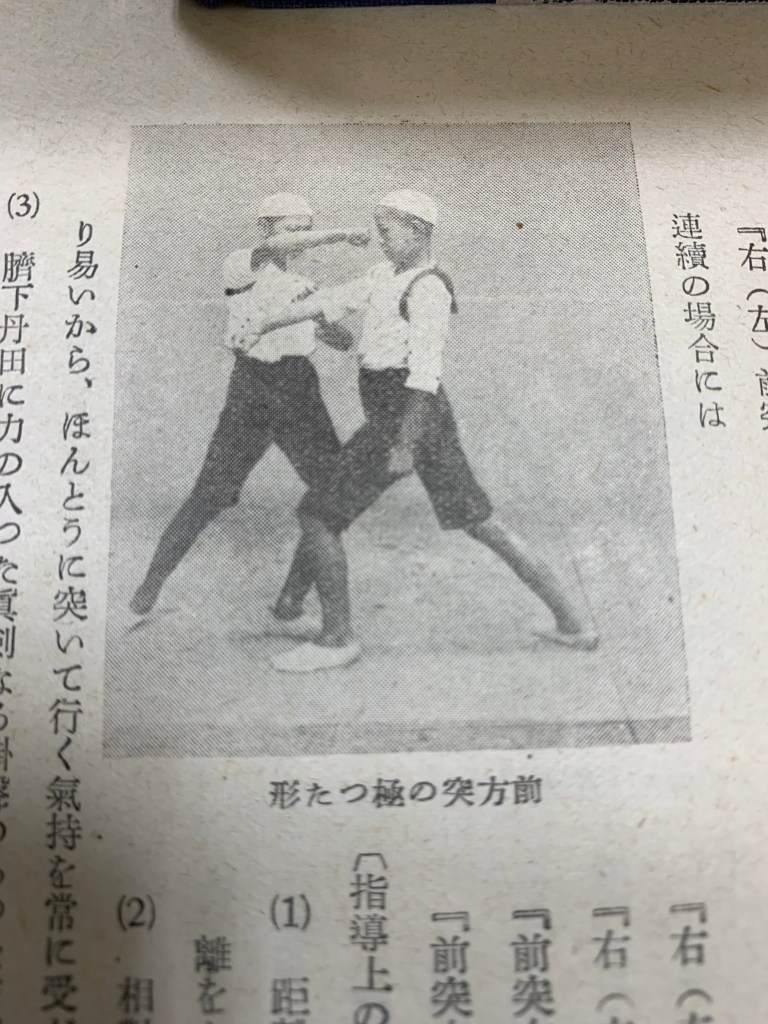

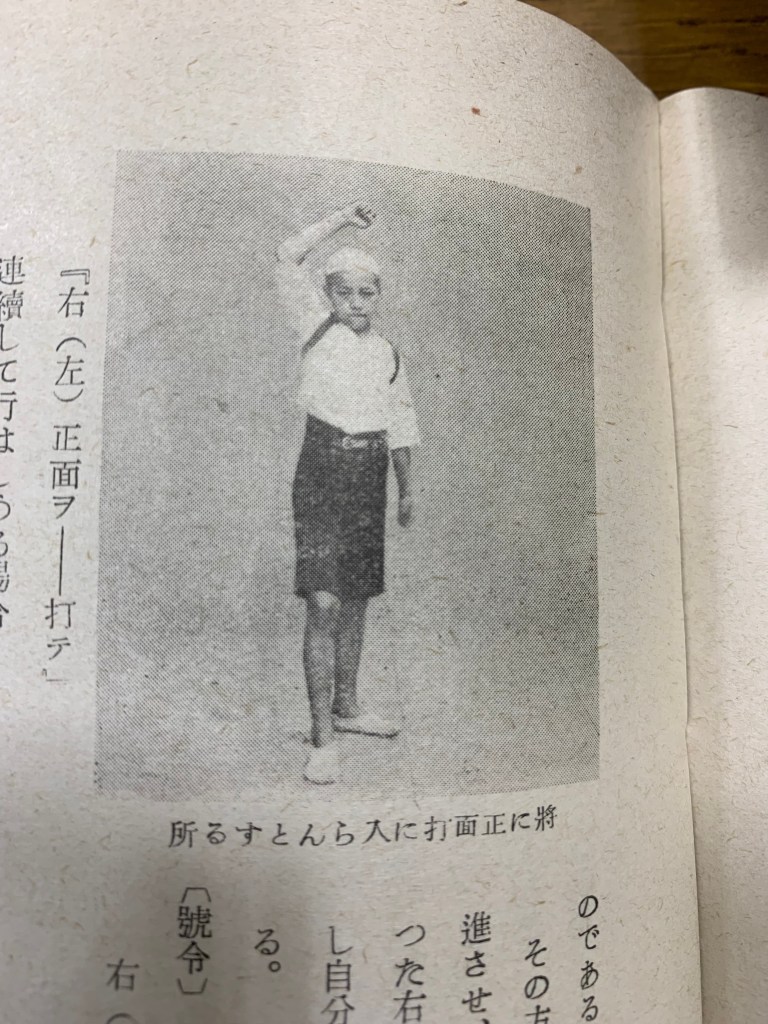

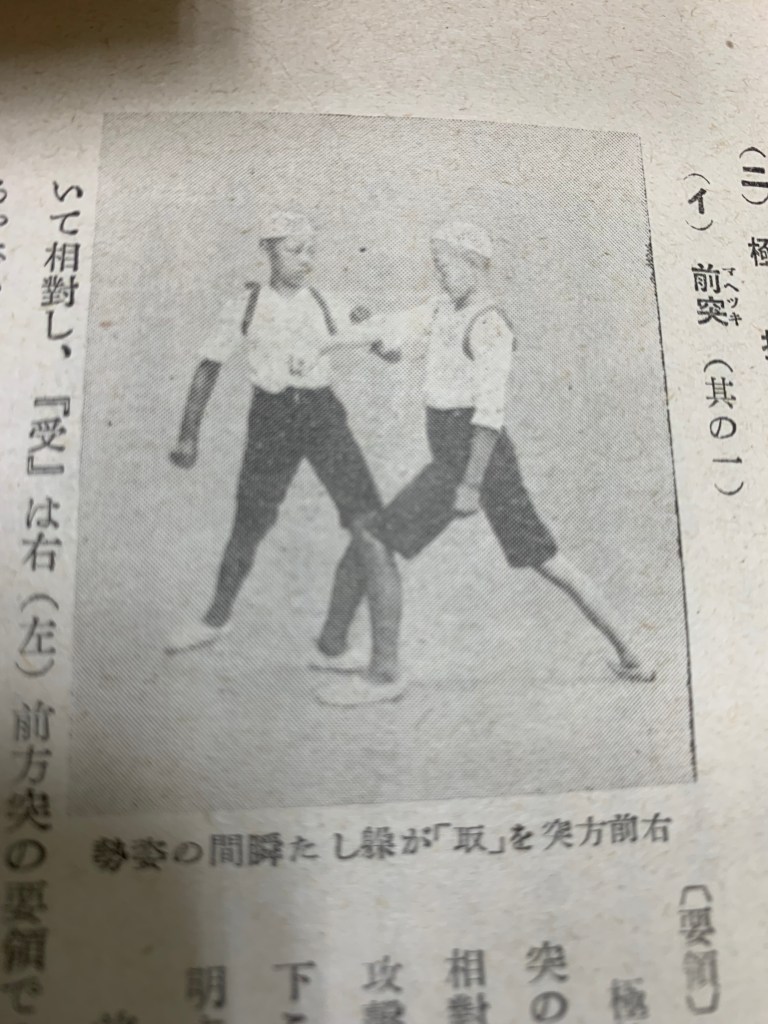

Pages from the book Kōbōshiki Kokumin Taiiku (1928)

Kanō’s interest in karate is said to have extended over a considerable period, and he is known to have closely examined its techniques (Kudō 2020: 42). Indeed, karate’s technical repertoire had a notable influence on Kanō’s thinking, contributing to the development of the aforementioned attack and defense forms (Koyama et al. 2021: 177–180). In particular, atemi-waza (striking techniques) came to play an increasingly important role within jūdō, and by 1931, such methods were even adopted as a mandatory component of school physical education in Japan (Kudō 2020: 39).

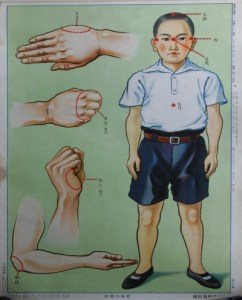

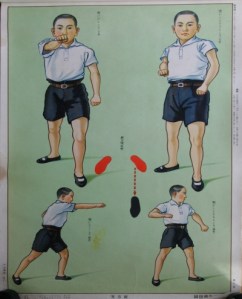

A publication titled Jūdō shidō kakezu (Jūdō instruction wall chart) from the Tōkyō Higher Normal School (dated circa 1939) by Kanō’s disciple Sakuraba Takeshi (櫻庭武, 1892–1941) vividly illustrates the physical exercises required of schoolchildren, using child-friendly drawings. These exercises, conducted twice a week for 30 minutes outside of regular class hours, were part of a broader program aligned with the increasing militarization of Japanese society in the late 1930s.

Pages from Jūdō shidō kakezu

(Source: 遊戯・スポーツ文化研究所)

Notably, the children depicted are shown in everyday clothing, emphasizing that no special uniform was required to perform the routines—an indication of the program’s intended accessibility and national scope.

Around the same time, the volume Shōgakkō Budō Yōmoku: Jūdō Kyōju Zenshō (1939), co-authored by Sakuraba Takeshi, also presented a range of relevant techniques with explanations.

Pages from Shōgakkō budō yōmoku jūdō kyōju Zensho (1939)

The influence of karate techniques is clearly discernible in all these photos and illustrations, demonstrating how Kōdōkan’s evolving system integrated elements drawn from karate. Admittedly, the title for this article is deliberately provocative. However, though peripheral to jūdō’s development, this episode offers valuable insight into karate’s early interactions with Japan’s martial institutions.

Sources:

Hosokawa, Kumazō / Mitsuyoshi Muroi / Takeshi Sakuraba (1939): 小学校武道要目 柔道教授全書 Shōgakkō budō yōmoku jūdō kyōju zensho (Elementary School Martial Arts Guidebook Jūdō Teaching Comprehensive Guide). Tōkyō: Shōgakukan (in Japanese)

Kanō, Jigorō (1928): 攻防式国民体育 Kōbō shiki kokumin taiiku (Offensive and defensive national sports). Tōkyō: Kōdōkan Bunkakai (in Japanese)

Koyama, Masashi et. al (2021): Karate. Its History and Practice. Translated by Alexander Bennett. Tōkyō: Nippon Budokan

Kudō, Ryūta (2020): 昭和戦前期における「武術としての柔道」論の展開: 当身技の研究に着目して Shōwa-sen zenki ni okeru ‘bujutsu to shite no jūdō’-ron no tenkai: Atemi-waza no kenkyū ni chakumoku shite (The development of the theory of jūdō as a martial art during the pre-war Shōwa era: A focus on the research of atemi-waza by Kanō Jigorō and his pupils), in: Budōgaku kenkyū 52 (2): 39–55 (in Japanese)

Niehaus, Andreas (2003): Leben und Werk KANŌ Jigorōs. Ein Forschungsbeitrag zur Leibeserziehung und zum Sport in Japan (Life and work of KANŌ Jigorō. A research contribution to physical education and sport in Japan). Baden-Baden: Ergon Verlag (in German)

Sakkō, No. 5 (1927), Tōkyō: Kōdōkan Bunkakai (in Japanese)

Sakuraba, Takeshi (c1939): 柔道指導掛図 Jūdō shidō kakezu (Jūdō instruction wall chart). Tōkyō: Tōkyō Higher Normal (in Japanese)

Yokomoto, Isekichi (1927): 琉球九州隨伴記 Ryūkyū Kyūshū suihanki (A Traveler’s Account of Ryūkyū and Kyūshū), in: Sakkō, No. 3: 27–37, Tōkyō: Kōdōkan Bunkakai (in Japanese)