The study of karate is multifaceted. In addition to its history, sports science, pedagogy, psychology, anthropology, sociology, philosophy, religious studies, media and film studies, researchers have also explored the physics of karate.

First studies

Scholarly interest in this subject in the Western Hemishpere likely began around the mid-1960s. On July 2, 1966, J. A. Vos and R. A. Binkhorst of the Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Nijmegen, The Netherlands, addressed this field in their article “Velocity and Force of Some Karate Arm Movements”, published in the British weekly scientific journal Nature. In their abstract they wrote:

A special aspect of Karate (a Japanese technique of self-defence and, in competitions, a game with very strictly regulated rules in which the partners are not allowed to strike each other) can sometimes be seen as a demonstration: the Karateka breaking bricks, tiles or blocks of wood with a strike of his bare hands, feet, fingers or forehead, the object being supported only at its ends.

Knowledge of the physical and mechanical properties and characteristics of karate was very limited — for the most part, virtually nonexistent. It was not until the 1970s that researchers began to revisit this field of study. For example in early 1975, Jearl D. Walker of the Physics Department at Cleveland State University analyzed the forward karate punch as an example of collision mechanics.

On May 23, 1975, Peter B. Cavanaugh and Jean Landa from the Biomechanics Laboratory, College of Health, Physical Education and Recreation, Pennsylvania State University, presented their study titled “A Biomechanical Analysis of the Karate Chop” at the Annual Meeting of the American College of Sports Medicine in New Orleans. In their presentation, they noted that “the sport of karate has been somewhat neglected by scientists.” Following the presentation of their nine-page paper, a more detailed article of the same title was published the following year in the Research Quarterly: American Alliance for Health, Physical Education and Recreation. In this study, the authors employed cinematography, accelerometry, and electromyography to analyze the pre-impact movements of the arm and trunk during karate chops intended to break pine boards.

Research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

In the following year, Richard S. Wilk, undergraduate student of the renowned Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, USA—an institution that has produced numerous Nobel laureates—also turned his attention to this subject. His bachelor’s thesis (1977), completed at MIT, was titled A Biomechanical Study of a Karate Strike.

Possibly building on his earlier thesis work, Richard S. Wilk, together with his thesis supervisor, the American physicist Michael S. Feld (1940–2010)—renowned for his research in quantum optics and the medical applications of lasers—undertook a more detailed investigation into the physics of karate. Their findings were published in Scientific American, a leading American popular science magazine in which figures such as Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla had also contributed articles. Another co-author of this landmark study was Ronald E. McNair (1950–1986), who completed his Ph.D. under Feld’s supervision. McNair was an accomplished karateka, having won a gold medal in AAU Karate, captured five regional championships, and earned a fifth-degree black belt. He later became a NASA astronaut, but tragically lost his life in the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion.

Science writer Jess Romeo (2021) later summarized their endeavor retrospectively for JSTOR Daily: “In the late 1970s, a team of karate-loving physicists decided to perform an experiment inspired by their collective passion for martial arts.”

The landmark study

In their article, Feld, McNair and Wilk take a close look at how a karate expert can break wood and concrete blocks with his bare hands. In their opening remarks (1979: 150), they note:

The picture of a karate expert breaking stout slabs of wood and concrete with his bare hand is a familiar one. The maneuver is so extravagant that it is often dismissed as some kind of deception or illusion. but the fact is that there is no trick to it. Even a newcomer to karate can quickly learn to break a substantial wood plank. and soon he would be able to break entire stacks of them. We have investigated in detail how the bare hand can break wood and concrete blocks (and by implication do similar damage to other targets) without being itself broken or injured.

What emerged was a fascinating and still widely cited study that revealed the physical principles behind the seemingly incredible ability of a karate expert to break wood and concrete blocks with his bare hands. The article combined physics and biomechanics to measure the speed, force, and energy involved in various karate strikes. The researchers found that a trained karateka’s hand can reach velocities of 10 to 14 meters per second and deliver forces exceeding 3,000 newtons—depending on the technique performed. By applying models of stress, strain, and elastic modulus, they demonstrated that blocks break because the lower surface stretches and cracks first under tension. Their calculations showed that breaking a pine board requires roughly five joules of energy, whereas concrete requires about 1.6 joules, although it resists a much greater force. Using high-speed photography and dynamic modeling, they observed that the hand and target remain in contact for approximately five milliseconds, and that the human hand’s bone and muscle structure allows it to withstand forces far greater than those experienced in such impacts. They also explained why multiple stacked blocks can be broken more easily than expected: once the first block fractures, its two halves move downward with angular momentum, helping to break the next blocks in the stack. Overall, the study elegantly bridged martial arts and modern physics, showing that karate’s power stems not from mysticism or illusion, but from a precise combination of timing, coordination, biomechanics, and the remarkable capabilities of the human body.

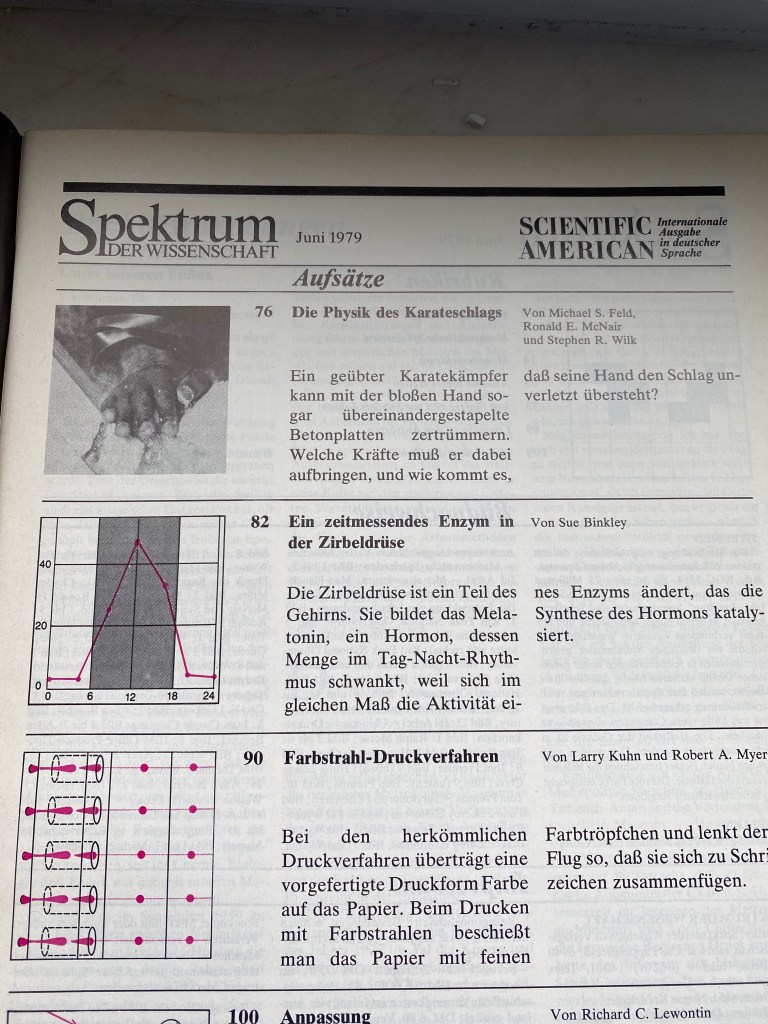

table of content

The article was translated into German later that same year under the title “Die Physik des Karateschlages” (The Physics of the Karate Strike) and published in the international German-language edition of Scientific American, Spektrum der Wissenschaft, in June 1979. In 1984, their work was even translated into Japanese.

The subject clearly continued to captivate the authors. In September 1983, they published another study under the same title, further analyzing the physical aspects of a karate strike and its interaction with the target. This follow-up paper examined several previously unexplored dynamical and biomechanical questions, expanding on their earlier investigation into the physics of karate. In their introduction (1983: 783), they write:

In recent years, the martial arts has experienced a revitalization and achieved worldwide popularity. It is extraordinary that as early as 2000 years ago ancient Oriental priests, warriors, and physicians devised systems of weaponless self-defense that make nearly optimal use of the human body. Many of the stances and techniques employed are totally different from the combat methods of the Western world and are often counterintuitive. The ways in which animal movements were studied and incorporated into exercise forms, and the gradual infusion of militaristic and religious doctrines which led to karate, tae kwon do, tai chi, and other Asian fighting arts are well documented. Karate itself developed in Okinawa in the early 17th century when the Japanese conquered the island and confiscated all weapons. In order to continue their feudal practices, the Okinawans developed a system of combat based on the weaponless Chinese fighting methods. The Japanese word karate means Chinese hand or empty hand. Today these ancient techniques, along with the associated rituals and mental discipline, are practiced throughout the world. Though some variations have been introduced in modern styles and methods, the fundamentals of karate techniques remain unaltered and the development of these techniques follows the same general scenario as in the ancient systems.

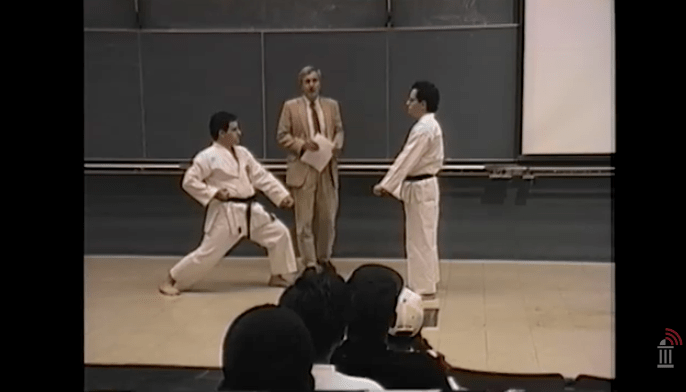

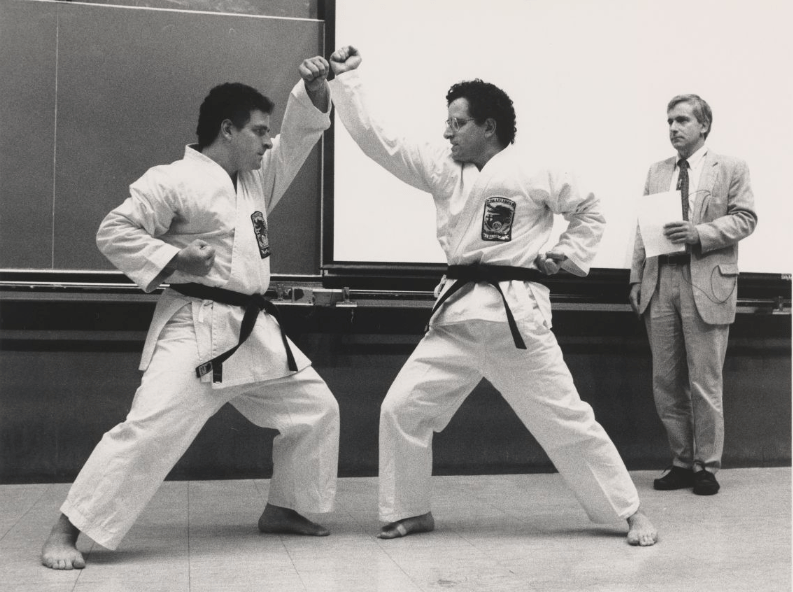

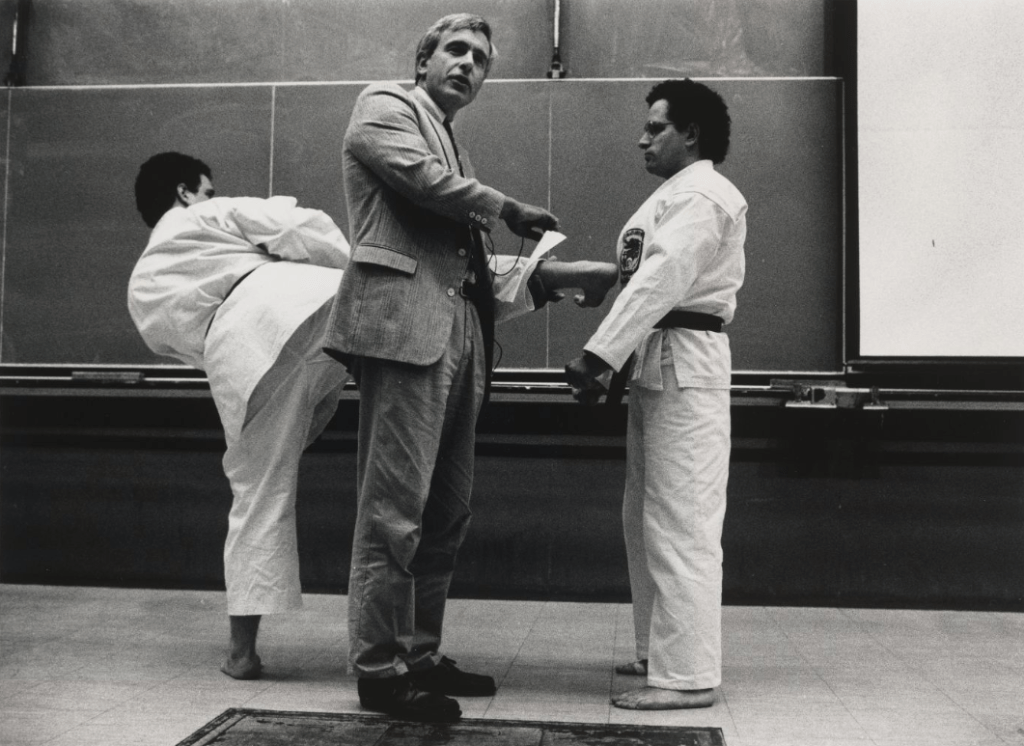

In 1991, Michael S. Feld returned to the topic in a university lecture, which is available in full on YouTube. In this presentation with live demonstrations, as part of his Introduction to Physics class — dedicated to the memory of Ronald E. McNair —, he revisited and expanded upon the findings of the 1979 and 1983 studies on the physics of karate.

Remembering Michael S. Feld

“Ron [McNair] became Michael’s karate master. Michael delighted in illustrating the physics of karate with classroom demonstrations like breaking a wooden board with a swift blow. And when Michael stopped advancing at the brown belt, he encouraged his sons to persist to obtain black belts, showing that the true master is the one who helps others to achieve their best,” recalled Edmund Bertschinger, head of MIT’s Department of Physics, in Michel Feld’s obituary.

Michael S. Feld lecturing about karate in 1991 (Courtesy MIT Museum)

Similarly Charles H. Holbrow in the Journal of Biomedical Optics (2011) remembered Michael S. Feld: “Michael supervised McNair’s thesis work, and McNair taught him and his twin sons karate. Michael earned a brown belt; Jonathan and David became black belts. McNair’s death in the 1986 explosion of the Challenger Space Shuttle was a deep personal loss for Michael. It was typical of Michael that once he had begun a project like learning karate, he would merge it with his interest in physics and push it to its limits. He liked to tell how, having agreed to give a Christmas lecture on the physics of karate, “…I was gripped with terror—I realized that I had just agreed to give a lecture on a topic I knew nothing about! Motivated by fear, I began a crash research program, including taking strobe movies of karate strikes.” The results were presentations at two national meetings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), two published articles about the physics of karate—one in Scientific American— and freshman physics students who were delighted by his classroom demonstration of breaking a stack of eight boards with his fist.”

Widespread recognition

Over the years, further studies on this subject have appeared — in various languages. Yet the 1979 study remains a landmark contribution, still regarded as pioneering today. Google Scholar lists 81 papers citing it, while the 1983 publication has been cited 94 times, surpassed only by Jearl D. Walker’s 1975 analysis of the karate strike, which has received 104 citations.

The article’s influence even reached the classroom: in January 1985, George A. Amann and Floyd T. Holt, teachers at F. D. Roosevelt High School in New York, wrote in The Physics Teacher (1985: 40): “While searching for a method to emphasize the magnitude of these forces, we happened to see the excellent article on karate in the April 1979 issue of Scientific American, by Michael Feld, Ronald McNair, and Stephen Wilk. After reading their careful analysis of the forces acting and the energy required to break objects with a karate blow, we decided to try to apply this as a demonstration during our discussions of the law of impulse-change momentum.”

All of this is highly fascinating: it shows how karate has become an object of serious scientific inquiry from multiple perspectives — something that most practitioners, and certainly the old masters of the past, would never have imagined. The exploration of the physics of karate, exemplified by the influential work of Feld, McNair, and Wilk, has thus become an enduring part of modern karate history.

I would like to thank the MIT Museum for kindly granting permission to use photographs from its archives.

Sources:

Amann, George A. / Floyd T. Holt (1985): Karate demonstration, in: The Physics Teacher, January 1985, pp. 40–

Cavanaugh, Peter R. / Jean Landa (1976): Biomechanical Analysis of the Karate Chop, in: Research Quarterly. American Alliance for Health, Physical Education and Recreation, Volume 47, Issue 4), pp. 610–618

Feld, Michael S. / Ronald E. McNair / Stephen R. Wilk (1979): Die Physik des Karateschlags, in: Spektrum der Wissenschaft, June 1979, pp. 76– (in German; original translated by Hans-Georg Märtl)

Feld, Michael S. (1984): 空手の物理学 なぜ素手でコンクリートが割れるのか Karate no butsurigaku naze sude de konkurīto ga wareru no ka (The Physics of Karate: Why bare hands can crack concrete). Tōkyō: Nikkei Saiensu (in Japanese)

Romeo, Jess (2021): The Physics of Karate, in: JSTOR Daily, February 26, 2021

Vos, J. A. / R. A. Binkhorst (1966): Velocity and Force of Some Karate Arm-movements, in: Volume 211, Issue 5044, pp. 89–90

Walker, Jearl D. (1975): Karate Strikes, in: American Journal of Physics 43, pp. 845–849

Further reading:

Di Maria, Giovanni (2021): Physics in Karate, EDN, May 13, 2021

Rist, Curtis (2000): The Physics of. . . Karate, in: Discover Magazine, January 2, 2000